Welfare or rights, advocate or activist—the language you choose to describe your work on behalf of nonhuman animals (hereafter referred to as animals) determines who finds, identifies with, and supports your work.

Increasingly, popular media has honed in on the expansion of language to describe traditionally animal-derived food products like vegan cheese, plant-based burgers, and oat milk. These conversations are important, but they’re conversations about products and marketing, not about the individual animals themselves.

In fact, the question of how we talk about animals remains fairly well restricted to the animal advocacy movement. Even then, inconsistencies and blind spots remain.

Consider this document a primer on how we can reframe our language to better advocate for animals in articles, social media posts, and other media. Whether you’re a researcher drafting a paper, an activist writing up a post, or a content creator writing materials for your brand, language matters. I want to help you choose it consciously regardless of where your ethical views lie.

This information is based on my experience as an animal welfare scientist, and my six years as a researcher, writer, and editor in animal advocacy.

Describing Yourself

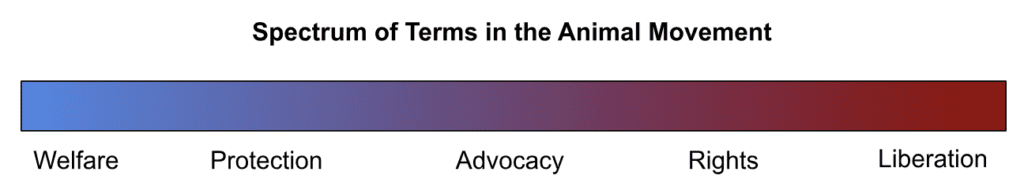

There are a handful of terms available to describe your work. My experience places these terms on a spectrum, with animal welfare being the most conservative and widely accepted term. On the other end of the spectrum, animal liberation (which may also be called abolitionism) is less positively viewed, and often seen as leftist and radical (though, as you’ll see below, this doesn’t mean it’s “bad”).

While all the terms on the spectrum are related, their differing positions mean they tend to describe different things. In theory, animal welfare concerns itself with the human duty to care for animals, whereas animal liberation concerns itself with animals’ agency. Though their efforts are usually complementary, equating these terms may lead one to overlook the strengths and weaknesses of different terms on the spectrum. For example, proponents of animal welfare can limit the good they are capable of by objectifying the animals in their care, limiting the quality of that care to pursue their own interests. Likewise, animal liberationists who do not acknowledge the importance of animal welfare science can fail to meet the welfare needs of the animals in their care. To summarize, the words you choose to reflect your work impact who sees it, how others in the movement see your work, and can affect how you view the work of others in the movement.

Table 1. The Spectrum of Ethical Positions Within The Animal Advocacy Movement

| Term | Description | Example Organization |

| Welfare | An area of scientific study that judges good care based on an animal’s physical and mental health, and the naturalness of their environment. The science as it is known today emerged in the 1960s in response to concerns for the well-being of animals in industrial agriculture. Organizations using this term tend to work in partnership with animal industries to improve conditions. | Shrimp Welfare Initiative |

| Protection | Less well-defined, protection may be used by nonprofits that advocate to improve animal welfare within current systems. However, they may exert more pressure on industry than welfarists. | World Animal Protection |

| Advocacy | A very broad term that may include elements from across the spectrum. As a result, it is often used as an umbrella term for everyone across the spectrum. It may also refer to indirect efforts to help animals, such as promoting or developing alternative proteins. | Animal Advocacy Careers |

| Rights | The philosophical belief that animals deserve the right to a life free of human exploitation, analogous in many ways with anti-speciesism. Organizations that use this term place greater pressure on and are more critical of animal industries. Individuals that identify as proponents of animal rights may be called “militant.” | Nonhuman Rights Project |

| Liberation | The philosophical belief that animals deserve the right to a life free of human exploitation, analogous in many ways with anti-speciesism. Organizations that use this term place greater pressure on and are more critical of animal industries. Individuals that identify as proponents of animal rights may be called “militant.” | Animal Liberation Front |

Similarly, the way you label yourself (e.g., as an advocate or activist) and what you eat (e.g., vegan or plant-based) also trickles into the perception of your work. Depending on the receptiveness of your audience, terms like activist and vegan can bring with them more radical and, unfortunately, negative connotations. This isn’t always true, though, and using these more radical terms in receptive circles can bring about conversations that center on animal individuality and agency. It’s your job to determine if your audience is receptive enough to have these conversations, or if more conservative terms would enable more effective change.

Describing Animals

Basic Changes for Everyone

Although the way we talk about ourselves is important, how we talk about animals is even more so. Regardless of your place on the spectrum, referring to animals as persons instead of objects will support your mission as an animal advocate. Although many self-professed animal lovers wouldn’t consider Fido or Fluffy as property, many people continue to objectify animals simply by following grammatical rules, with a few exceptions. But language changes with time. Like the growing normalization of ‘they’ to refer to an individual non-binary person, we should also update how we refer to animals. Animal advocates should, at a minimum, refer to an animal as ‘who’ instead of ‘that’ or ‘which’, and ‘they’ instead of ‘it’.

Along with this fundamental change in language, all advocates should ensure that the plural forms of animal names differ from the singular. This may seem blatantly obvious. However, the plural and singular forms of some animal names are the same. To be clear, I’m not advocating for you to alter moose to mooses or meese. Moose are large, charismatic animals that are not exploited and commodified on an enormous scale. Conversely, commercial fisheries and farms kill trillions of fishes and shrimps every year. Yet, the grammatically correct plural (i.e., fish and shrimp) lumps them together as a nameless mass. The same can be said for individual species within these groups (e.g., salmons, mackerels, etc.).

Finally, while we often refer to animals as though they are separate from humans, they aren’t. Referring to animals as “nonhuman animals” (or “non-human animals”) and “other animals” are all simple ways to close this divide. If, like me, you find that this makes your text excessively wordy at times, you can follow this example:

In the story, nonhuman animals (hereafter referred to as animals)…

Note: Although the term “fishes” is generally considered incorrect, it is sometimes used by industry and scientists when referring to multiple species. For example, “there are twelve species of fishes in the tank.“

Industry Terminology: What It Hides, When to Use It, and When To Lose It

If you work in animal welfare or animal protection, you’re likely familiar with animal industry terms that objectify animals or soften and disguise the realities of their experiences. While using these words might garner more trust or understanding with industry audiences, the objectification and deception implicit in their use is counter to the animal advocacy movement’s goals. Using accurate, neutral language is an effective way of avoiding these terms while still remaining in these spaces.

As language evolves over time, the ways that industries refer to elements of animal exploitation change as well, so it’s important to identify themes rather than individual terms. The four primary themes I’ve identified so far include:

- Animals as Plants

- Animals as Food

- Juvenile Animals as Adults

- “Killing” Euphemisms

The sections below offer examples of language along these themes, describe what they mean and offer alternatives. Depending on your audience and the search terms they use, you may prefer to retain the industry terms in some way. For example, the term “seafood” clearly objectifies aquatic animals but is more commonly used than “aquatic animals.” In this case, I would suggest referring to the industry term once at the beginning of a document, then stating that you will use another term. For example, “culturing salmons (hereafter referred to as farming salmons)…“

1. Animals as Plants

Table 2. Words for Practices and Animals That Characterize Animals as Plants

| Industry Term | Description | Alternative |

| Harvest | “In terrestrial animals, it refers to slaughter and butchering. In aquatic animals, it refers to the process of pulling animals from the water and letting them asphyxiate or slaughtering them.” | “For terrestrial animals: “slaughter” or “kill.” For aquatic animals: same as above but add “catching” or “handling” depending on context.” |

| Seed | Used to describe semen of farmed aquatic animals. | Use either “milt”—another industry term—or “semen.” |

| Ripe | Refers to sexual maturity. Usage seems exclusive to aquatic animals but does not appear to be a common term. Example here. | Use “sexually mature” or “fertile.” |

| Culture | “Refers to farming aquatic animals.” | Use “farming” and “farm” or “breeding.” |

2. Animals as Food

Table 3. Words That Describe Animals as Food Products

| Industry Term | Description | Alternative |

| Seafood | Aquatic animals killed in wild capture fisheries or farmed in aquaculture. | Use “aquatic animals” to refer to the group of animals consumed in the most broad sense. However, since this group describes hundreds of species, adding further detail like, “crustaceans, fishes and bivalves,” may be better depending on context. |

| Broilers | Chickens selectively bred to grow dangerously large very quickly so they can be slaughtered for meat. | In academic or other circles that work with industry, “broiler chick” is more accurate (more on this below). In advocacy or rights circles, use “chickens bred for meat” or the breed’s name: Cornish Cross. |

| Layers | A short term for laying hens, or the chickens selectively bred to produce eggs year-round at the expense of their health. | In academic circles, “laying hens” is appropriate. If this is too wordy, use the method described in Industry Terminology, followed by “hens.” Alternatively, use the breed or strain name. |

| Dairy cows | Cattle selectively bred for milk production at the expense of their health. “Cow” specifically refers to females, although it is often used to describe all individuals in the species Bos taurus. | This is a tricky one. Aim to be as specific as possible, without equating the animal’s identity with the food product. For example, use “cows bred for dairy” to refer to females and “bulls bred for dairy” to refer to males. Alternatively, use “cattle bred for dairy” to refer to a mixed group. You can also use the breed name (e.g., Holstein or Jersey). |

3. Juvenile Animals as Adults

Lamb and veal may clearly refer to the bodies of juvenile animals (i.e., animals that are babies, teens and anywhere in between). However, most animals, particularly those killed for their flesh, are killed well before they reach adulthood. The most obvious example of this is broiler chickens, who are as large as laying hens but still peep like chicks by the time they reach the slaughterhouse. Whenever possible, advocates should highlight the age of animals being discussed, particularly if they are unable to alter language through other means. For example, rather than referring to “broilers” or “broiler chickens”, it would be more accurate to call them “broiler chicks.” Similarly, you may choose to refer to “juvenile pigs” going to slaughter instead of “pigs” or “finishing pigs.”

4. “Killing” Euphemisms

You’ve probably heard the phrase ‘meat is murder.’ Depending on where you lie on the spectrum, your reaction to this may be anywhere from an eye roll, to a shrug, or an enthusiastic nod. But while this expression may be infamous, it should be joined in infamy by terms that disguise or soften the act of killing. Killing is killing, no matter the victim.

For all the terms described in the table below, use “slaughter” or “kill” as an alternative. Academic audiences may find slaughter more acceptable, but because its use is normalized in nonhuman animals, I consider “kill” to be the most neutral and preferred term.

Table 4. Words to Avoid That Describe Killing Animals

| Industry Term | Description |

| Depopulate | The mass killing of animals, usually on a farm. Although it might sound like moving animals from one building to another, the methods used in depopulation prioritize efficacy or biosecurity over the pain animals experience. Examples include ventilation shutdown, suffocating in foam (i.e., foaming), or burying animals alive. |

| Cull | The first definition for this word is “selecting from a group.” Further definitions refer to killing off wild animals to whittle their numbers, or killing a farmed animal from a larger group. In other words, it objectifies the animals in question. |

| Exterminate | Although it can refer to killing humans in select circumstances, it is most often used to describe killing animals that wander into and, unfortunately, damage human homes (i.e., “pest” animals). If you run a humane wildlife control business, this term may be too important to avoid. Use the strategy outlined at the beginning of Industry Terminology. |

| Euthanize or Euthanise | This term is only appropriate when referring to the compassionate killing of an animal to relieve them from unavoidable suffering. It should, under no circumstances, be used to describe killing animals on-farm or at the end of an experiment to prevent their prolonged suffering. Experimenting on and farming animals are not unavoidable activities. |

| Sacrifice | Often used in animal experimentation, this term alludes to animals’ deaths serving a higher purpose. Although I sympathize with the contradictory feelings experienced by those who use animals in experiments, this term implies a degree of reverence that animal subjects do not experience. If you want to acknowledge the animals you connected with in your research, I would suggest individualizing them in your writing using the methods in this article. |

| Destroy | This term may be used to describe killing animals who are no longer useful. However, it is the most objectifying term in this list. We destroy objects, not sentient beings. |

Inflammatory Language Choice: The Pros and Cons

On the other side of the spectrum, language used by animal rights and liberation activists rarely, if ever, runs the risk of objectifying animals. However, if you identify with this side of the spectrum, your words should still be chosen with care. Poorly considered language runs the risk of backfiring by alienating your audience and/or making you appear insensitive to the plight of other oppressed groups. Writing consciously about animals means that your language choices are empathetic to their experiences as well as to the receptivity of your audience. With that in mind, the table below examines some more commonly used inflammatory terms and provides suggested reading that will help you avoid mistakes and better understand your audience.

Table 5. Words for Practices and Animals That Characterize Animals as Plants

| Inflammatory Term | Neutral Alternative | Could This Harm a Vulnerable Group? | Suggested Reading |

| Murder | “Kill” | Unlikely | How Do People Feel About Non-Speciesist Language? |

| Kidnap | “Forced separation of mother and child” | Unlikely | How Do People Feel About Non-Speciesist Language? |

| Holocaust | “Mass killing” | Yes | Who’s Harming Whom? A PR Ethical Case Study of PETA’s Holocaust on Your Plate Campaign |

| Slavery | “Depending on context, “exploitation” or “forced labour” | Yes | Social Movement Lessons From the British Antislavery Movement |

| Rape | “Sexual exploitation” or “sexual abuse” | Yes | Feminism and Husbandry: Drawing the Fine Line Between Mine and Bovine |

Final Thoughts

No matter where your beliefs or work lie on the spectrum, the language you use has profound impacts on the animals you advocate for. Language choice can feel trivial at times, but it is the root of culture, conveying our values and beliefs to our peers and loved ones. Implementing the linguistic changes described above will support your mission to bring attention to animals’ individuality and experiences. More importantly, it can change the way people perceive animals and the things we subject them to.

This isn’t a comprehensive list of terms, and as language evolves and new technologies and practices emerge, new words will arise. If you think a word or pattern of language is missing from this article contact me.