The printing press, the telephone, and the internet represent some of humanity’s greatest inventions. They each amplified our ability to communicate, accelerating the exchange of knowledge and ideas. Today, communication is a fundamental part of knowledge exchange: researchers write reports, papers, theses, and more. For the individual, these texts can represent achievement, expertise, and prestige. Yet, the true value of research lies in how it can benefit society; to be a benefit, it must be well communicated.

Propelled by the launch of the Internet, academics’ access to research has exponentially increased since 2000. Consequently, academics are publishing—and under more pressure to publish—than ever before. While greater access to knowledge brings many benefits, it also creates a challenge: we have the same amount of time in a day to sift through far more information than ever before. Search engines and AI tools may help us find the information we seek more effectively, but the researcher remains responsible for evaluating the relevancy and quality of information. To do that, they must read.

Quality vs. Quantity of Research

Unfortunately, academics, scholars, researchers, and scientists—no matter what they call themselves—are not known for producing accessible writing (i.e., high-quality writing or high readability text). Even without jargon, academic papers are often prohibitively difficult to read for native English speakers. In fact, research examining the readability of science between 1881 and 2015 found that it was steadily declining. Now that international collaboration in the sciences is common, poor readability likely poses an even greater barrier to effective science communication.

This low readability is not without consequences. We may not always notice a well-written paper, but poor writing may lead readers to draw any number of conclusions about the author. As Conrad, 2019 says, readers may see poor-quality writing “as a show of disrespect for one’s reader; as resistance to improving one’s writing ability or one’s English in general; as a poor reflection on one’s instructor, supervisor, or institution; or—perhaps most concerningly—as an indication of intellectual inferiority.”

More importantly, because communication is at the heart of knowledge-sharing, poor readability can lead readers to misinterpret research methods or bring them to the wrong conclusions, effectively harming two pillars of science: reproducibility and accuracy.

“It does not matter how pleased an author might be to have converted all the right data into sentences and paragraphs; it matters only whether a large majority of the reading audience accurately perceives what the author had in mind.”

Gopen & Swan, 2018

Prioritizing Quality Writing in Research

But are the benefits of producing more readable, accessible scientific works worth the time and money? To answer this question, I searched the literature on the topic, specifically looking for the effect of readability on being cited, attaining publication, and acquiring funding.

Citations

The number of citations a work receives is often used as a proxy for its visibility and impact. Before we dive into the impact on readability and citation number, keep in mind that the citation and readability studies summarized in the table below do not answer the following questions:

Who is reading these articles?

Examining the attention that articles receive from non-experts and experts, Jin et al., 2021 analyzed the effect of language complexity on the Altmetric scores (a measure of attention across websites) of articles published in Science. They found that specific measures of readability were associated with the most attention. Specifically, articles that used a variety of uncomplicated words, and that used more complex nominals and less verbal phrases, were correlated with higher Altmetric scores. The study also pointed out differences in attention between non-experts and experts, suggesting that experts in a field likely tolerate more linguistic complexity than non-experts. This relates to the point below.

Why are these articles being cited?

Academic writing is well-known for its complexity. At times, the complexity of language may be falsely equated with the quality of content. This is reminiscent of the argument by gibberish and alphabet soup fallacies.

How are these articles being cited?

The studies below do not consider how research is cited. It may or may not be true that papers with lower readability scores are more often cited for information in their abstracts or introductions rather than their results. As far as I know, this has not been studied. However, Guerini et al., 2021 studied the readability of the most downloaded and most bookmarked articles, and compared their readabilities to those in a control group. They found that the most downloaded articles had higher readability, whereas the most bookmarked articles had lower readability. These findings seem to imply that readability impacts how articles are cited.

Table 1. The Effect of Readability on the Number of Citations a Paper Receives.

| Paper | Sample Characteristics | Findings |

| Ante, 2022 | Articles published up to 2020 concerning one of twelve technologies. | More complex texts received at least one citation, and highly cited articles tended to be more complex. |

| Guerini et al., 2021 | Physics and astronomy papers published “in the last decade” that are retrieved from (1) a most cited or (2) a random group. | No difference in readability between the most cited papers and the random group of papers. |

| MacCannon, 2019 | Articles published in the American Economic Review in 2000–2009. | The least readable papers (those in the fifth quintile) received ~155 fewer citations. |

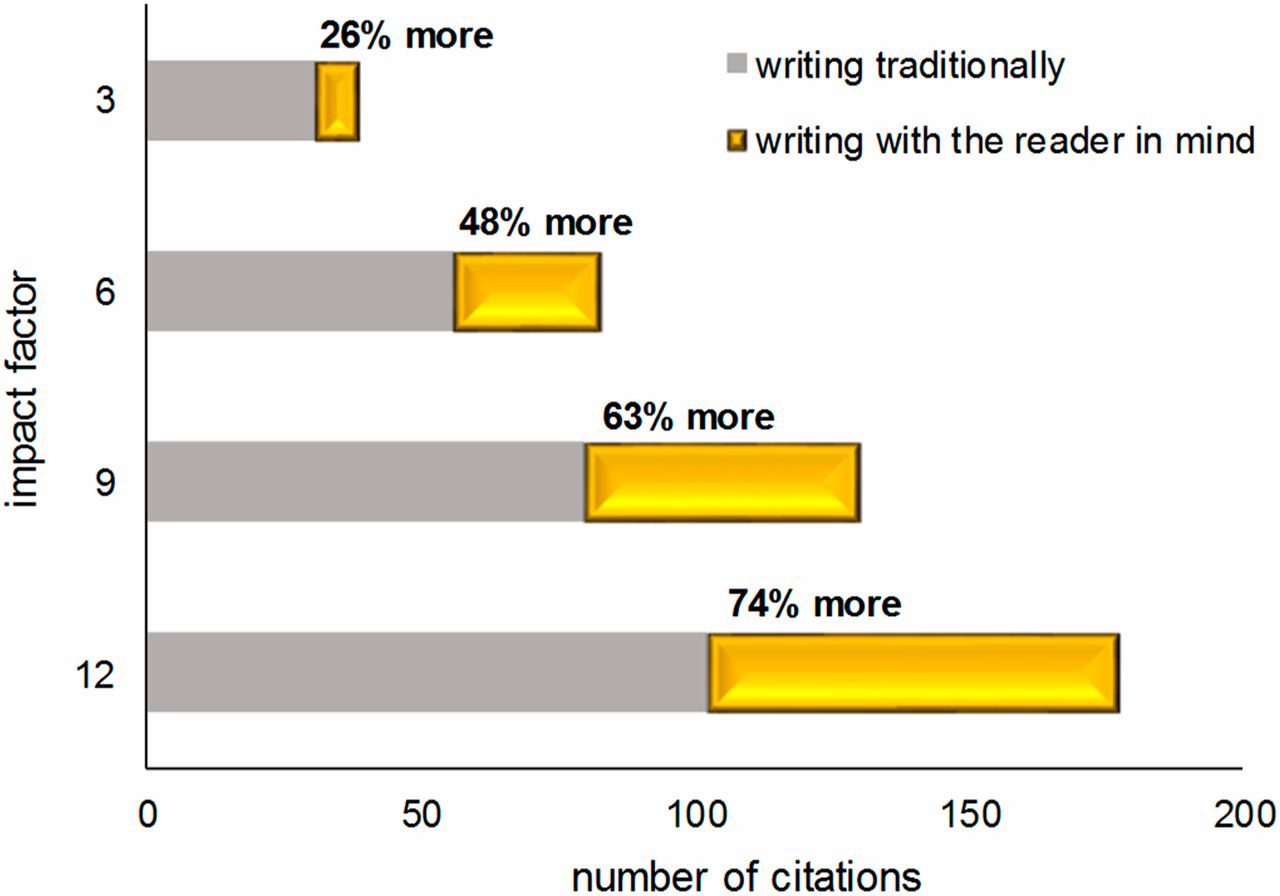

| Ryba et al., 2019 | Environmental, medical, and social science articles published in 2012–2013, controlled within each field by topic. | Readability increased the number of citations; the higher the impact factor of the journal, the more readability increased citation number. |

| Dowling et al., 2018 | Articles published in Economic Letters in 2003–2012. | Readability was associated with more citations, especially for math-heavy papers. |

| Lei & Yan, 2016 | Articles published in four information science journals in 2003–2012. | No effect of readability on citations. |

| Didegah & Thelwall, 2013 | Biology, biochemistry, chemistry, and social science articles further classified by subject and published in 2000–2009. | No effect of readability on citations. |

Three papers found no effect of readability on citation number and four found an effect. Of those four, one found an inverse relationship between readability and citation number, two found a positive correlation, and another found that the least readable papers (those in the fifth quintile) received fewer citations. This last finding is arguably still in favor of readability, without showing a linear relationship.

However, MacCannon points out that studies on readability and citation numbers may be misleading, as these studies only examine papers that have met publication standards. Therefore, readability may actually have a larger impact on research than the articles above suggest. To find out, we will examine how readability affects the chance of being published.

Publication

I found three papers that address the effect of readability on whether research is published. The strongest evidence comes from Fages, 2020, who found that the readability of economics working papers (papers not yet published or peer-reviewed) was positively associated with being published in one of the top five economics journals. Furthermore, as Ryba et al. found, readability and the journal impact factor work together to amplify citation number. Consequently, the value of submitting high-quality writing to a journal could be substantial. It should be noted, though, that Ryba et al. and Fages examined different academic fields.

Like journal acceptance, readability has been found to affect the acceptance of conference submissions. Roth, 2019 examined the number of reviewer comments related to copy editing issues in manuscripts submitted to a large conference. The study found that submissions accepted as oral presentations had the highest frequency of positive comments and the lowest frequency of negative comments related to copy editing. Conversely, manuscripts that were rejected had the lowest frequency of positive comments related to copy editing. To summarize, better outcomes correlated with good writing, not a lack of bad writing.

Finally, Feld et al., 2024 evaluated the impact of editing (and thus, readability) on reviewers’ opinion of a text. They found that reviewers judged edited papers to be of higher quality overall compared to unedited papers. Reviewers also viewed edited papers as more likely to be accepted to a conference and/or journal. In fact, editing increased the likelihood of conference and/or journal acceptance to a comparable or greater level than any of the following alone:

- Having been a colleague of a referee at a journal;

- Having been a colleague of an editor at a journal; or

- An all-male authored paper compared to an all-female authored paper.

This suggests that increasing the readability of papers may help overcome some barriers in academic publishing. It also suggests that time and/or money spent creating high-quality texts may be particularly valuable for academics who are women and/or early in their careers.

So, improving the quality of writing in papers can help academics publish successfully, and it could also increase the number of citations their papers attract. But is its value limited to publishing, or do other pursuits within academia benefit from high-quality writing?

Funding

A 2022 study conducted in Europe, with a minority of native English speakers, found that writing quality had a moderate effect on the success of a grant. Specifically, higher quality writing in the project description and CV, but not in the abstract, was associated with improved chances of success.

A US study published in 2018 that examined writing quality in National Institutes of Health (NIH) proposals found similar results. Unsurprisingly, it also found that the match between an applicant’s past work and the work in the proposal (i.e., applicant-proposal alignment) was a predictor of proposal success. However, proposal success was more impacted by the quality of writing than by applicant-proposal alignment—although it should be noted that the analysis of writing quality had a smaller sample size.

Final Thoughts

Beyond these markers of academic success, improving writing quality also improves more important, less measured outcomes. Clearer writing demands clear messaging and logical flow, but we cannot transfer these to the page without first grasping them ourselves. In that way, creating high-quality text improves the quality of the writer’s thoughts and reasoning. And when the writer understands their work and writes clearly, readers experience greater understanding and confidence in their knowledge. Thus, high-quality writing enables both the refinement of one’s own knowledge and its transmission, two elements that sit at the very heart of why we do research.

Academic research is a public good. High-quality research has the opportunity to build new lines of inquiry, affect market participants and charitable donors, and even influence policy.

MacCannon, 2019